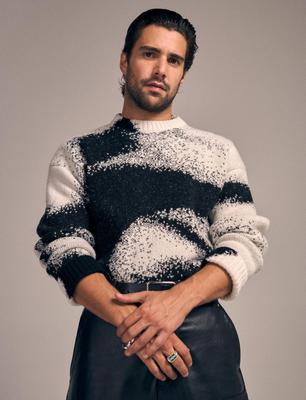

David Jonsson Talks Origins & Rye Lane for WONDERLAND

For a 16-year-old David Jonsson growing up in East London, an acting career was not always the plan. Jonsson (a self-proclaimed introvert) surprised both himself and his mum when he told her he wanted to become an actor. “Well stop shouting about it then,” she replied. “Go and do it.” 10 years later, Jonsson’s acting resume is the reflection of a man dedicated to his craft.